Li Junfeng

— Early Years —

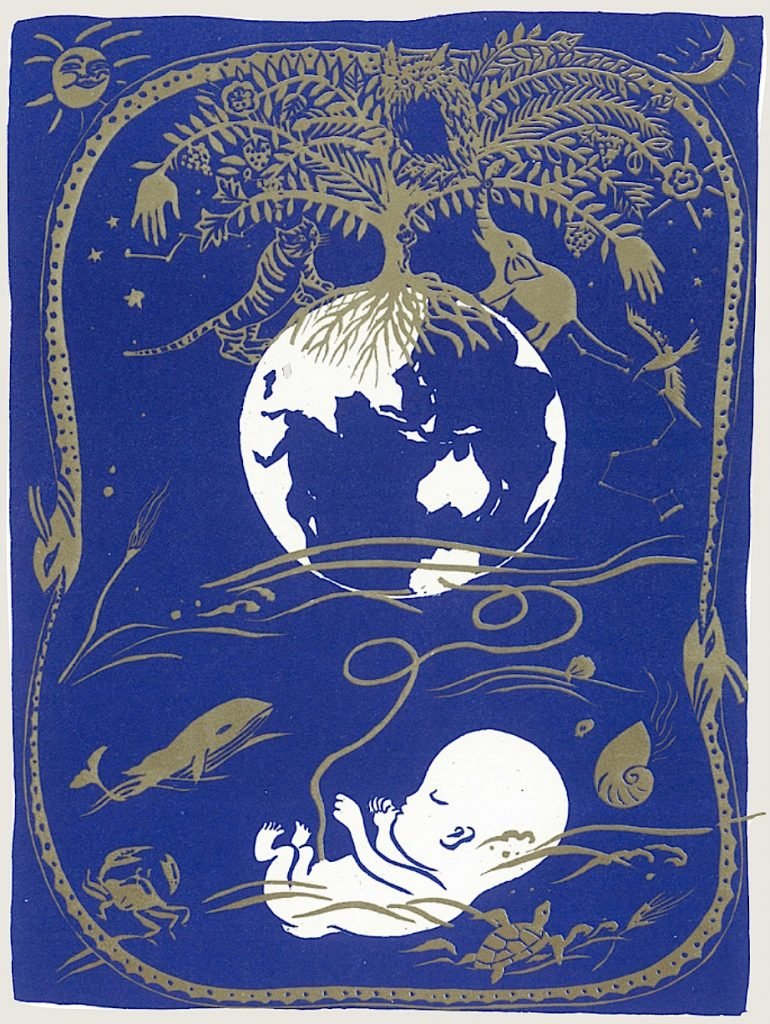

Origins of Big Heart

(Interview with Julian Gresser/April 2015)

Note to our Readers:

Qigong Grand Master Li Junfeng is a living exemplar of Laughing Heart’s exuberant vitality. At 78 he is as spry as a mountain goat. He travels around the world and according to him is never jet lagged even after 20 hour flights. As all true masters he is continuously learning and perfecting his art. He shares these never before published personal insights of his life’s journey in the hope of inspiring other explorers.

Master Li Junfeng–Profile

Li Junfeng achieved initial prominence as the head coach for over 15 years of the Beijing Wushu Team and the National Wushu Team of the People’s Republic of China. Under his leadership and collaboration with Co-Head Coach Wu Bin their teams won over one hundred gold medals and numerous other laurels and brought great honor to the country. During these years he also achieved national fame as a martial arts movie actor and director. Master Li is an innovator of world stature who has made a unique contribution in integrating China’s great martial arts tradition and advanced practices for health and longevity within a comprehensive body of knowledge and experience based on the principle of unconditional love (博爱养心) Master Li is currently Chairman of the International Shengzhen Society Foundation. During the past twenty-five years he has developed a network of certified teachers in over 30 countries, and visiting over 70 countries where he has offered training program.

(JG) Master Li, what are some of your earliest memories?

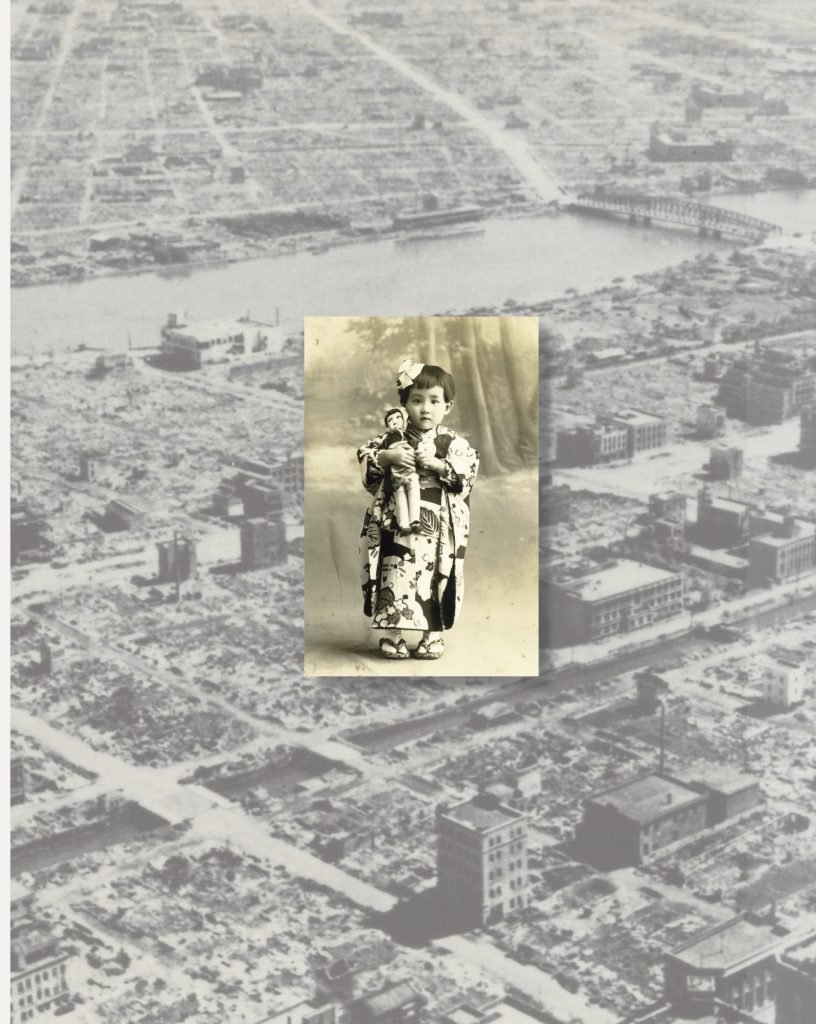

(LJF) I was born on October 13, 1938, in the Year of the Tiger, in Hebei Province, China. My grandfather was a Chinese doctor. Our family was relatively well off, but like many families we suffered greatly during World War II. My father joined a local militia, fell ill, and died when I was a month old. I was raised by my mother and grandparents. I admired my grandfather greatly and wanted to become a doctor like him.

From my earliest years I loved Chinese martial arts. Many people in our village practiced martial arts, and I loved the movements and the beauty of the forms. In our elementary school there was a wonderful teacher who had been a friend and classmate of my father in high school. He encouraged me very much to practice martial arts, and also sports, music, and other art forms.

I joined the student council in high school, and as a member, one of my responsibilities was managing the riflery team. Since I had no experience shooting rifles, I was required to learn. In 1957 after a few months of training, I entered the Si Jia Zhang City Riflery Competition and won first place, and afterwards joined the city riflery team. I participated in a province-wide competition and won second place. In 1958 I joined the Hebei Province Riflery Team, and remained a member for nearly two years. The demands of the team meant practicing riflery all day, to the exclusion of other classes. Because I wanted to attend a university for college, I left the riflery team in December of 1959 and returned to high school.

When I went back to Shi Jia Zhang First High School to study, there was a nationwide food shortage and the government issued food ration coupons. I was often hungry, especially after the special food I got on the Hebei Province Riflery Team. I had a friend on the riflery team, Liu Zhi Qang, who left Shi Jia Zhang city to join the team at the same time I did, and returned to school at the same time, though we attended different schools. One day he found a food ration coupon in the street, and with no way of returning it to the person who’d lost it, he traveled across town to find me and share 100g of bread with me. Though he certainly could have eaten it all himself and probably still been hungry for more, he chose to share it with me. This really moved my heart, and I’ll never forget him or this demonstration of unconditional love. Even now, I still miss him and remember him fondly. I still keep his photo with me.

In the summer of 1960 I graduated from high school and took a college entrance exam. I still wanted to attend medical school and become a doctor like my grandfather, but at the time, universities that taught Athletics, Art, or Music had priority selecting students. The Physical Education University of Beijing recruited me after my initial exam, and accepting this invitation meant I could enroll right away with no further examinations.

In college I majored in Wushu, (Chinese Martial Arts). Wushu was a very popular major, and I started my college education with a large class of peers. In my third year, the university selected a few distinguished students to become members of the University Wushu team, and I was among them. This was quite an honor. Our team performed wushu exhibitions for foreign dignitaries from all over the world.

In 1964 a French television crew visited China and came to our school, and filmed me for the Paris Channel 2 feature, A Day in the Life of a University Student in China, which was broadcast in France. The crew recorded my daily routine and gave me my first experience of being on film.

Lost in the Desert: A Taste of Flour Soup

(JG) I get the impression that your life was relatively easy and uneventful in those days.

(LJF) Actually, those days were not easy. In fact, I almost died in 1962. In the early 60s there were three years of calamitous natural disasters that caused a serious famine in China. Even in the cities food was scarce. Though we ate better than most, even the athletic department lacked food. In our university many people suffered from edema as a result of malnutrition. This is why the national athletics department formed the National Hunting Team. Because of my experience with the Hebei Province Riflery Team, I was conscripted to join along with members of the national riflery team, and sent on a hunting expedition into Xinjiang province to hunt yellow sheep and to provide food for our starving people. Xinjiang is an autonomous province in far northwestern China on the border with Mongolia and Kazakhstan. The hunting team consisted of marksmen and motorcycle drivers.

Every day we hunted from dawn until dusk. It was winter, and the cold was so severe that the sheep froze almost as soon as we shot them. The government had strict rules about hunting: we were not allowed to hunt during calving season, and we could only use single shot rifles in order to protect the sheep population.

My partner was a professional motorcycle driver, and he drove a motorcycle that had a modified sidecar to carry cargo while I shot sheep. The two of us worked very well as a team. One day we went to hunt in the area around an old oil rig that everyone recognized as a landmark. At dusk we headed back to our base camp which was very far away.

We hadn’t shot many sheep that day, and on the way back we came upon a large herd and decided to continue hunting. We followed the sheep for a long time. Our sidecar was already full of sheep, night was falling, and we were very far from our base camp. I thought we should return to the oil rig, since we knew the route back to our base camp, but my partner thought we could take a shorter more direct route to the base. I reluctantly agreed and we used a compass to locate an old track, which we followed until the ground became too soft and our motorcycle could go no further. We unloaded a few sheep to lighten the load, but the motorcycle was soon stuck in the sand again. We left a few more sheep and proceeded a little further, but the same thing happened so this time we had to unload all of the sheep. But still we couldn’t make any progress through the soft sand. At this point we decided to stop for the night.

Our team’s emergency procedure was to make a signal fire if lost at night, since it would be visible for miles in the desert. But when I suggested that we start a fire we realized, to our dismay that my partner (who was responsible for carrying our lighter) had leant it to a friend. Needless to say this was a dismaying realization.

We couldn’t sleep because there were wolves in the area and we had to stay alert, with our guns ready. The temperature dropped precipitously with nightfall to well below freezing. It was very dark. We had no light, no food, no water, and no shelter. Our uniforms were insulated so we tightened our coats, but we could not sleep, we could only wait for morning. Thank God no wolves came around that night. We were lucky.

When morning arrived we climbed a nearby hill, and from the top we could see the oil rig. We tried to start the motorcycle but it wouldn’t work because the oil was frozen solid. If we had had a lighter we might have melted the oil to create a fire.

We reasoned that if we could see the oil rig clearly, we must not be too far away from our comrades, so we left the motorcycle behind and started walking. But we misjudged the distance as the rig was still far away, and because our uniforms were heavily insulated, our progress was slow. Also we were very tired and hungry from lack of food and sleep. We walked all day, stopping frequently to rest. We became really exhausted and tried to use dried brush we found as improvised walking sticks. We encouraged each other to keep moving towards our goal, promising that we would rest once we got there. We finally reached the rig at dusk.

We had assumed that when we got to the oil rig we would find someone there, but there was no one. At this point our spirits really began to sink, but we were grateful to find a primitive room used by workers where we could take shelter. It was still very cold but at least we were protected from the wind. The room had a door and we were very pleased we had a way to keeping the wolves outside. We made mats of dried vegetation and fell asleep.

We spent the third day in the rig waiting for someone to find us but still no one came. That night we could hear wolves baying and prowling in the vicinity, so we barricaded the door and put our backs to it, and slept fitfully with our guns at our side.

(JG) I can’t imagine how you survived. Didn’t you panic? Weren’t you in a lot of pain not eating or drinking for several days?

(LJF) By the fourth day, we were feeling a little panic, but we kept our spirits up by telling each other jokes. “Maybe we are going to die,” I said, “but if we don’t die, I think we’ll have a pretty good story to tell. We’re both our parents’ only children, so we can make a compelling movie for them.” We joked with each other in this way to keep from losing heart.

By the end of the fourth day we began to really feel the effects of starvation and dehydration. Several times we thought we heard approaching engines and people talking, and we’d run outside, expecting to greet our rescuers, only to find no one. We were so thirsty we had the idea to drinking our own urine, so we found an old, dirty bottle, but by this time we were so dehydrated that we could not even produce any urine. A few snowflakes fell from the sky and we tried to catch them in the air and lick them from the ground, but ended up with more sand on our tongues than water. But we were grateful for even a tiny drop of moisture which gave us great relief.

That night we began to hallucinate. We’d hear the sound of motorcycles and voices and people calling for us, but when we looked outside the oil rig, there was nothing but empty desert. At this point we really began to despair. That night we talked about the dire predicament we were in, and I said, “I’m my mother’s only child, and my father is dead. If I die, she’ll be devastated. So I can’t die here. We must conserve our energy.” From that point we stopped running outside every time we thought we heard someone approaching, and we stopped talking very much, and remained lying down or moving very much.

The fifth day we spent in this way dozing on and off.

On the sixth day we again heard sounds outside and roused ourselves to go outside, hoping to find someone, but again, it was just a hallucination. We still believed our team members would find us, but we stopped talking entirely to conserve the little strength we had left. If we thought we heard rescuers approaching, we stopped telling each other, and instead took turns peeking out the door. But the sounds were only the workings of our imagination.

Close to dusk we heard the sound of a motorcycle, but we didn’t bother, assuming it was another hallucination. The voices persisted. I slowly got up and looked outside. This time I saw a few parked motorcycles and people walking around. With our last burst of energy we ran outside, shouting. Chinese don’t ordinarily hug, but we embraced our teammates with great bear hugs, and everyone was in tears. It was almost dark and we climbed on the motorcycles and returned to our base camp.

On the way back to camp one of my teammates offered me a radish, I tried to chew but I could not swallow, so we waited until we returned to camp to eat. Our leader made us some flour soup. It was easy to eat, easy to digest, and the taste was better than anything I’d ever tasted. I drank only flour soup throughout the next day, too. I’ve never loved food so much in my life. Sleeping in a tent was also an exquisite pleasure. I understood then that happiness is completely relative– having simple food, not freezing, or being eaten by wolves made me very happy. It was more than enough. I still love flour soup very much and I know how to cook it. Actually, before we go to class let me make you some flour soup. (He starts cutting vegetables and making the broth.)

My comrades later told me they knew we were somewhere near the oil rig, and they went back to look for us, and searched a long time for our signal fire, but never found it. On the second day they returned and searched again, but still had no luck finding us. We explained that we didn’t have a lighter, and had traveled far from the oil rig by the second day, out of visibility and earshot, and we didn’t get back to the oil rig until dusk on the second day. When they couldn’t find us they thought we must have left the area and searched a wider perimeter, but still couldn’t find us. They were on their way back to camp when they stopped to rest at the oil rig. I told them we were inside the room, and they said they checked the room on the first and second day, so didn’t feel they needed to check again since it was empty before. All of our problems would have been solved by a lighter.

(JG) That’s quite a story. Surely, at sometime during this saga you must have been worried?

(LJF) No, I didn’t worry. From my heart I believed in my team. My comrades knew where we were heading and they knew about the oil rig.

(JG) Did you feel any anger?

(LJF) No, we didn’t feel any anger at all. We felt that our comrades had probably already come to the oil rig when we were lost in the desert, and had waited all night for us, but of course we weren’t there.

(JG) What about the driver? Didn’t anyone blame him?

(LJF) No, no one blamed him. The driver loaned his lighter to a local person in kindness, and forgot to get it back. At that time the locals in Xinjiang province had never seen a lighter before, and they were very interested in it. His heart was in the right place. He was just forgetful and never expected to get lost in the desert.

(JG) Why did your friends return to the same place after they had already looked for you there?

(LJF) Ah, that was a bit of luck. They went back to the oil rig simply because they were tired and wanted to rest. They didn’t expect to find us.

(JG) I wonder whether this is how Big Heart opens a place for chance to happen. Did you draw any life lessons from this experience? It almost seems like a parable?

(LJF) Yes, this experience deeply influenced my life. My first lesson was to be prepared. When you go into the desert you need a lighter and not only one lighter – a lighter for each person! And you need water, and food – these things are important. I also learned to say “No.” I knew my comrade’s short cut was a very bad idea, but I didn’t want to conflict with him. Sometimes you must hold your ground when you know the correct way. I learned to pay attention to small things. In the desert small things can save your life. I discovered also that happiness is relative. This is a very important lesson. I can tell you I was never as happy and appreciative in my life as when I tasted that flour soup after having nothing to eat or drink for five days! My experience in the desert also helped me to understand suffering. When you suffer, you don’t always know whether it is leading you to a good thing or a bad thing. Sometimes the worst pain of our life gives rise to many good things. After suffering in the desert, I can appreciate everything, even really simple pleasures like food and shelter. I can be flexible; eat anything, sleep anywhere. Also, when you have a hard time, out of nowhere people help you. Through hard times we can make very good friends. Now I love flour soup. Look, the flour soup is ready. Let’s enjoy it together.”

First and Last Love

(LJF) After I graduated from high school the government appointed me to the Beijing Shi Sha Hai School. After I registered, but before I started teaching, the government sent me to do community service in a remote mountain village for more than a year. I worked and lived among poor farmers who opened their homes to me. We worked very hard and survived on subsistence rations with no meat, rice, vegetables or even wheat flour, and no fuel for heat in winter. We had to wear hats indoors to protect our ears from frostbite. The entire village shared two small wells, so each family shared a single pot of water for a day for washing.

When the Cultural Revolution began, the community service program was cancelled, and I returned to Beijing and joined the revolution. During the revolution we had no classes, the country was in chaos. It was anarchy. I witnessed many terrible things during that time. Every organization – schools, factories, hospitals – were divided into two factions, a rebel faction that fought against the organization’s leadership, and a conservative faction that was for it. The Beijing Shi Sha Hai School was no exception. I was among the new coaches returning from service assignments in remote villages. We had no experience with the school and so no ideas about our leader. We just wanted less conflict. As a group we started a third faction – the neutral faction. Our focus was on ending conflict. We were lucky that we’d been sent away before we had students, because during the Cultural Revolution many students fought against their teachers, but we managed to avoid being in that situation. We just tried to make peace in our school.

(JG) It seems like a very Spartan existence. Did you have any personal life? What about girls?

(LJF) In those days it was very difficult to meet girls. Because the school had cancelled the wushu program and stopped enrolling students, we taught small, free, informal wushu classes. I had a student who was also a personal friend, who invited me to her home to introduce me to one of her colleagues named Yanfang. I asked another wushu coach to join me, because I was shy. After thirty minutes I excused myself to go to the bathroom, which was a public facility on the street. The other coach joined me. My real motive was to give Yanfang and her colleague, the matchmaker, a chance to talk. The other coach asked me if I liked Yanfang and I said, yes, I liked her very much. He preceded me back to the apartment and let the matchmaker know. She told him that the feeling was mutual and he relayed this information to me. So Yanfang and I both felt the same way, but didn’t discuss our feelings with each other until I walked her home. In those days it was dangerous to walk alone on the street at night, so as I accompanied her, she asked, “Are you really sure?” and I said, “Yes, really sure.” And that decided it. We became boyfriend and girlfriend that night and had a simple wedding ceremony a year later. I never looked at another girl again, and she never looked at other boys. We still love each other very much! (He starts to laugh.) This was our destiny – to love each other.

Training Stories

(LJF) During the Cultural Revolution, when the wushu team was cancelled, we were sent to do different jobs in the school. I was assigned to work in an office, other people taught football, and others became warehouse workers. After the Cultural Revolution, in 1971 we started wushu classes. During that time we only had two coaches, Wu Bin and me. We were friends in college and had a very good working relationship. He was a year my senior and I respected him, and he trusted me very much.

Our first enrollment was in 1971 and again the following year we had another enrollment. Our students began training at ages 9-13. We looked for the same essential qualities in prospective students — physical strength, a suitable physical symmetry, agility, and a keen intelligence. We knew when we saw a certain light in their eyes. We interviewed their teachers to find out if they had discipline. Wushu was an extracurricular activity, so students trained in the afternoon after a full school day. Our students improved very fast.

Wu Bin and I proposed to the government that we form a Beijing Wushu Team but our request was at first denied. In 1974 our students, representing Beijing city, competed in the national wushu competition and won the group championship. The same year China formed two national teams, one went to the US to perform at the White House, and the other gave an exhibition in Japan. Most of the national teams were comprised of our students and Wu Bin and I became the national wushu team coaches. We wrote a letter to the Beijing Athletic Department and they finally agreed to form the Beijing professional team.

Wu Bin’s coaching style was very strict, although he was a kind man. After we formed the Beijing Wushu Team, we divided the students into men’s and women’s teams, but our goals were essentially the same – to build champions. From 1974 our team won group champion continuously for 12 years. Group champion meant everybody got gold medals. Our team won more than 100 individual gold medals during the same period.

(JG) Can you tell us some stories about your coaching days? What were some of the secrets of your success?

(LJF) Before I do that I need to tell you about an event that happened many years before that shaped my philosophy of coaching. On my riflery team we had a very demanding, disciplined coach who trained us very hard for the shooting competitions. But he was so strict that he demanded an immediate response from his students whenever he blew his whistle. One day the whistle blew and I rushed to respond, but the surface I ran on was uneven and I broke my ankle. Although I recovered rapidly I placed second in the province-wide competition, but I am certain that if I had not been injured, I would have placed first. I learned from this example that it is very important to be disciplined, but never to excess. It’s important to be strict and precise, but always to pay attention to safety. And never rush, always remain calm and attentive.

(JG) I agree with you. This will be an important theme our book, especially the relationship of Big Heart and Mind to the emotions. It is very interesting to understand how these ideas were shaped by your life experience. So what were your secrets?

(LJF) I will tell you about my approach to training and coaching.

First, basic training is very important. But this is not simply a matter of hours devoted; quality is more important. We had very high standards and a precise training method. We could accomplish better results with our focused methods than many hours of training with the alternatives. We trained part by part and step by step to ensure the foundations were very sound. Each form has different basics; all of the weapons forms and regional styles had their own fundamentals.

Second, different people respond to different treatment. We always adapted the training method to the individual needs of the student. One size never fits all. People have different physical strengths and personality traits. Some students need to be driven, others require support. Some are better suited to certain weapons or styles, so we found the right fit, but even two students practicing the same form must be treated as individuals. The nuances of their performance will be different, so we had to identify their unique talents and then play to their strengths.

Third, Strict management. This means making people become very disciplined and very focused. When the student becomes focused, they bring more energy to their training and improve faster, and they understand their coach’s instruction.

Fourth, we cherished our students like our own children. When they were sick, we never sent them to the hospital alone. I put them on the back of my bike and took them there. We would help them take their medicine and discussed their condition with their doctors and parents. For example, one student who won many gold medals came down with hepatitis. This was a very serious illness. We interviewed several doctors, and I asked them, “What is your strategy to cure hepatitis?” And we listened carefully, and helped the family select the best doctor. And during her treatment we took care of her, just like I would care for my own daughter. A journalist wrote a story about this incident, declaring, “Coach Li cured his student’s hepatitis!” So, many people called me to find a cure, and I had to tell them, “I’m not a doctor, go to the hospital and ask!”

Another girl had a bad tooth, but she had an even bigger problem – the dentist fell in love with her, and started making advances. We had to speak with the dentist and remind him to behave like a professional. We settled this matter without conflict. Another student fell in love with this lovely girl, but she was suspicious and asked me to help her. So I talked with this boy and he said to me, “Coach Li, I really love her, please trust me. I am serious.” And I could see that his heart was good and I believed him. They got married and now have several children. Today she is coaching the gongfu club at Stanford University.

The parents appreciated our approach because we were not only teaching martial arts; we were helping our students understand the meaning of integrity.

Fifth, My co-coach Wu Bin and I were very close, like family, like one heart. We always helped and learned from each other, and we always shared good things and supported each other through hard times. Though we divided the job, we always cooperated, and our team’s success was our unified goal. We always trained and practiced together.

Sixth, We were open-minded and understood that valuable knowledge could be found outside of conventional circles. We always tried to learn as much as we could from any available source, whether it was other coaches or traditional wushu masters.

I loved all my students very much and even today when I visit them in San Francisco, Berkeley, Portland, Singapore, Manila, Beijing and other cities they regard me as their second father.

(JG) Do you have children, and do they also practice martial arts?

(LJF) In 1973 my daughter Li Jing was born, and then two years later, my son Li Hai Chuan, nicknamed Jack. From an early age, Jing loved martial arts and at 8 years old she began serious training at Beijing Shi Sha Hai School. Her coach was one of my former students. After 3 years she became a member of the Beijing Wushu Team and participated in national competitions. She later competed in the Asia Games and international competitions. She studied at a university in the Philippines, and now lives in Germany, and she teaches Sheng Zhen Gong in Europe and assists me with international teacher training. Jack was interested in music and the piano, but my wife and I did not know anything about piano. We did what we could to support and encourage his interest. He was passionate about music and found a teacher by himself. He studied in China and then went to the US and studied piano for eight years and got two Master’s degrees, one in piano and one in art management, and a D.M.A. in performance and teaching. He now works at the Music Institute of China. So I’m lucky I have a son and a daughter.

Fame and Stardom

(JG) Tell us now about what caused you to become involved in movies. After all, it is an unusual career change, especially as you became a national film star so rapidly.

(LJF) I always loved movies, but I never expected to become involved personally in the film industry. Sometimes in life when your heart is open and you help others without asking anything in return, something good happens. It was that way with my film career.

In 1982 The Beijing Movie House decided to make a wuxu movie, Wu Lin Zhi, and asked me to help search for a star. The director contacted me through our school. He was compiling a list of candidates, so we met and I went with him for a month all over China, even to remote provinces, and interviewed various martial artists and coaches. The main character was a very special person; in fact the movie title in English was The Honor of Dong Fang Xu or Pride’s Deadly Fury. It was about this good person, a person of integrity who has all of these difficulties and must make great personal sacrifices, and has many battles, but because of his skill and integrity he prevails, and even becomes friends with his chief antagonist, who is a real bully in the beginning.

After auditioning many, many martial artists – we even went to the national wushu competition to scout potential actors – the director said to me, “I know the best person for this role; I have an idea.” But he did not tell me anything more about it. We returned to Beijing and after a few days the director and producer went to my school without telling me and started making inquiries. That day one of my students was on her way to the bathroom and she overheard the director speaking with the school principal, saying that he was very interested in casting me for the role. My student rushed back to the gym to tell me, “Coach Li, the director is thinking of selecting you for the lead role!” I said, “Impossible, I don’t believe you. Stop joking.” After training, my principal called me to his office and told me they’d agreed to send me to the Beijing Movie House to star in the movie, but that I’d still have to continue training the Beijing Wushu Team. If I could do both, no problem, but if I couldn’t continue to coach then I could not be in the movie. Of course I agreed to do both. I was happy to do the movie because I was familiar with the script and it was a good story that promoted wushu philosophy.

I immediately reported to the film studio and accepted the role. The director and assistant director ran through the script with me. When I asked, “Why did you choose me?” the director replied, “This movie is really about integrity, and we see that you understand this. You never once proposed yourself, or told us you wanted the part. It is important that the main actor understand the character of Dong Fang Xu, and therefore be credible.” Several other actors and coaches had reached the final round of auditions. We prepared for a few days and then returned to the studio to do screen tests. Then we were sent home to wait for the news of who would be cast in the role of Don Fang Xu.

After a few days I was notified that I’d been chosen. I returned to the studio to study the script and prepare for the role. Before shooting even started, the leader of the Beijing Athletic department decided I couldn’t do the movie, since it could put our team’s champion status at risk. I had no choice but to leave the film production. But the Beijing Movie House wouldn’t take no for an answer, so they went to the vice-mayor of Beijing and the leader of the national athletics department to intercede on their behalf. They applied pressure, and I was allowed to resume work on the film.

First we studied the script for many days, and the director asked me to write the story of Don Fang Xu’s life from early childhood so that I’d gain insight into his character. I wasn’t completely unfamiliar with the film industry, since I’d previously been a consultant action director for other films. I did a lot of research and asked actors I knew for guidance to prepare for my role. When filming began, I was very shy, and often broke character when the director shouted “Action!” But after three days the shyness vanished and I felt much more comfortable and confident. I’m grateful for this experience, since life is much more comfortable now that I can teach anywhere without feeling shy.

I continued to coach the team during off hours, and I explained to my students that they’d have to train even harder in my absence. They assured me that I could rely on them. The team had two captains, Li Xia and Ge Chun Yan, but Ge Chun Yan had been cast as the leading lady in the same film, and Li Xia said, “Coach Li, don’t worry, just go and make the movie. If you two are not here, I’ll lead the team and we’ll take our practice seriously. You can rest assured.”

(JG) It sounds like it was smooth sailing from then on. This story is interesting as it shows how potential conflicts were resolved in Chinese society in those days. It seems there were no hard feelings all the way round.

(LJF) Yes, there were no hard feelings. We worked in harmony. But once the movie was well underway a more serious conflict occurred which placed the entire enterprise in jeopardy.

There was one actor who felt he was being exploited since he didn’t get to keep his pay. It went to his company the same way that my wages were given to my school and everyone else’s pay went to the various agencies they represented. He told the producer that he wanted to be personally paid, but the producer refused on the basis that the studio couldn’t afford it. The movie was in the final stages of production, but if this actor refused to participate, it would never be completed. I talked to the rest of the cast and then approached the producer and asked him to give the actor in question just a little more money, and reassured him that the rest of the cast wouldn’t follow suit and demand more for themselves if he did. So he agreed, and the production continued, and the movie was completed.

In 1983 Wu Lin Zhi premiered in Beijing. It was an instant blockbuster. It won an award for an outstanding film of that year, and I went on stage with the director and accepted a trophy. It was the Chinese equivalent of the Academy Awards ceremony. From that time on many studios began approaching my school and I received many offers to play leading roles in films.

(JG) How did you feel about all this sudden fame?

(LJF) Actually, it was interesting in the beginning because it was novel and unexpected, but I soon found it very tiring. I felt all of the attention from fans and the press really limited my freedom and I longed to return to a normal life.

I continued to train my students very seriously while making the movie and the film took a hiatus while my team competed in the National Wushu Competition and won seven gold medals. After the film was completed the team competed again and did even better than before. This time we took ten out of a total of sixteen gold medals. This was an all-time record in the history of competitive Chinese martial arts on a national level.

(JG) How were you able to manage this? I can imagine playing a leading role in a movie and training a national level martial arts team each require enormous energy and mental concentration.

(LJF)—We did everything with heart; we always tried to do our best. I had this very strong sense that this director and also my school and students trusted me. I felt a deep responsibility and obligation to them. (He moves two oranges on the table in front of us to illustrate the principle.) You see these oranges? They represent my two jobs. When I was doing the movie, I focused all my energy and my heart on doing this job; and when I was training my students, I gave everything to them. This was the only way I could fulfill my obligation to them. The result was that each received perhaps even more of my heart and my attention than if this challenge had not been presented.

The Philippines

(LJF) In 1987 I was the only coach of the Chinese national wushu team. Our team participated in the Pan Asia Championships in Japan and won thirteen out of sixteen gold medals. At that time I received an invitation from the Philippine National Wushu Federation to train its team. But the Beijing government did not accept the invitation from the Philippines – they wanted to keep me with the Beijing wushu team. Negotiations continued for some time. In 1988 it was finally agreed upon – I was free to go to the Philippines and begin training its team. From 1988 until 1991 I was the chief coach of the Philippines National Wushu Team. This is how I came to make many friends in the Philippines who are very supportive of my work in Big Heart practice until this day.

The Inspiration for Sheng Zhen and Big Heart

As the years passed my passion for external wushu gradually evolved towards internal wushu forms, like bagua and taiji, which naturally also led to meditation and various styles of qigong. Also, I met several qigong masters in China and learned much from them, especially how to purify the Heart, and the relationship of Heart to Mind. In 1987 I learned a special meditation; Union of Three Hearts, and through the practice my understanding of human life deepened. In 1991 I was inspired to create the moving forms that comprise Sheng Zhen Gong. Through meditation I began to appreciate and understand the power of love in the world, love without any reservation or conditions. I started to develop my own practice combining many of the techniques and principles of martial arts with what I was discovering from inner practices. I developed a new kind of practice involving moving and still meditative forms which I called Sheng Zhen Gong, or as it is called in China today Bo Ai Yang Xin Xun Lian Fa. This perfectly captures the spirit in the title of our book, Big Heart. In 1992 I returned to the Philippines and in 1994 I dedicated myself to teaching Union of Three Hearts and the other Sheng Zhen Gong forms. I received a lot of support and interest from my friends in the Philippines, and in 1995 we founded the International Sheng Zhen Society.

From 1995 until today I have visited more than 30 countries to teach, and we have excellent certified teachers in many of them. In the beginning I lived in Manila, but for the past 12 years my wife and I have lived in Austin, Texas where I’m the dean of the Body and Mind Department at the Academy of Oriental Medicine. Jing lives in Germany and Jack teaches piano and music in Beijing.

(JG) That is a wonderful story. What is the next stage of your journey?

(LJF) I have had a strong intuition that Santa Barbara may be a very promising place to continue. I am very happy to have so many able and sincere students here. I am glad that we can develop this new framework together which we are calling “Big Heart.” I am happy to draw from my life experience and also yours, which is very different, and that we can work together with many new friends and introduce Big Heart practice in a very broad way, and continue to learn. This really was the essence of the vision of the vision I had when I moved to the Philippines, although Big Heart is taking a very interesting new form that I hope will appeal and be helpful to many people. Big Heart with Love– is the essence of our practice, what I hope for the world.

© Copyright Julian Gresser and Li Junfeng February 2017 , All rights reserved.